Jamaica: Decolonization project

An exploration of the gradual decolonization of Jamaica from Britain over several decades.

In many case studies of decolonization, the new countries are rapidly given independence and sometimes left to fend for themselves. In Jamaica, however, this trend did not take place. Instead, Jamaica—a former colony of Great Britain—was gradually given freedoms by the British over the course of decades, until finally being granted independence in 1962.

Our project seeks to answer the question: what effects did this gradual process of decolonization have on Jamaica, as compared with a more "traditional" rapid decolonization process?

We invite you to explore this website to learn more!

Key moments in the decolonization of Jamaica

-

1938

Widespread rioting occurred in the streets of Jamaica due to dissatisfaction with British rule and the general economic hardships that followed the Great Depression. Jamaican laborers were also upset with poor working conditions and low wages. This event set the stage for the independence movement to come, with many Jamaicans unhappy with the status quo.

-

1943

The 1943 election was a big victory for the Jamaican independence movement, as the Jamaica Labour Party (JLP) led by Alexander Bustamante won an 18-point victory to take control of the Jamaican House of Representatives. Bustamante advocated for autonomy of Jamaica and better conditions for its workers. In 1944, the Bustamante-led government implemented a new constitution that established universal adult suffrage and created a bicameral legislature, a proposal that was vetted and agreed to by the British.

-

1945

In 1945, The Moyne Commission was published by the British government, largely in response to unrest that had occurred in British Carribean colonies in the late 1930’s. The report revealed the poor economic and social conditions Jamaican laborers faced, leading the British government to grant Jamaica more freedoms along with creating a welfare fund to address the rampant poverty in the region.

-

1945-50

Following the end of World War II, the decolonization movement rapidly progressed on the local level. Local colonies in Jamaica transitioned from Crown Colonies to independent states, as nationalist fervor reached a fever pitch. The British government was content with these changes, anticipating the eventual independence of Jamaica.

-

1955

Norman Manley was elected Chief Minister in 1955, and proceeded to accelerate the process of decolonization. Manley passed constitutional amendments that established the basis for a cabinet of ministers in Jamaica, creating the structures of government that would rule the nation after independence from the British was granted. Manley also passed more home-rule laws, gradually taking control away from the British monarchy and putting it in the hands of Jamaican representatives.

-

1962

On August 6th, 1962, Jamaica became independent, while retaining the British monarch as head of state. This came after decades of frustration with British rule, and was initially hailed as a victory for the Jamaican people. Alexander Bustamante became the Prime Minister, witnessing his goal from decades prior come to fruition.

History of decolonization in Jamaica

Notes on key change-makers

Alexander Bustamante

_(cropped).jpg)

A prominent politician both before and after Jamaica’s independence, Bustamante played a pivotal role in founding modern day Jamaica. Bustamante first became known for his letters published in The Gleaner, a popular Jamaican newspaper. In them, Bustamante called out the social and economic disparity between the upper and lower classes and advocated for change. He was also a supporter and leader of the West Indian labor unrest of 1934 to 1939. The West Indian labor unrest was a series of labor strikes, riots, and other protests over the poor living and working conditions of the lower class. Much of the blame was placed on Denham, the colonial governor of Jamaica, and not the British. Bustamante himself stated: “Long live the King! But Denham must go,” and went so far as to argue that the British had little to no knowledge of Denham’s treatment of Jamaicans.

Bustamante was briefly a member of the People’s National Party but later founded the Jamaican Labor Party in opposition after a dispute with the leader of the People’s National Party. Bustamanate and his new party proceeded to win a majority in the 1944 Parliament. He had pushed for Jamaica to leave the West Indies Federation since the country joined and was successful; Jamaica left the Federation in 1961. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Bustamante began pushing for Jamaica’s independence from Britain which it gained in 1962. In the following elections, Bustamante, as the leader of the majority party, became the first Prime minister of Jamaica.

Norman Manley

Like Bustamante, Norman Manley was a champion of workers rights in pre-independent Jamaica. A supporter of trade unions and universal suffrage, Manley fought against the poor conditions most Jamaicans lived and worked in. He founded the People’s National Party in 1938 in order to better coordinate his efforts and worked closely with Bustaname until the latter formed his own political party. Although the People’s National Party lost the first election, they eventually gained a majority in 1955 and Manley became the Chief Minister (later Premiere), a position resembling that of a Prime Minister until 1962.

Manley was a supporter of Jamaica's participation in the West Indies Federation but was forced to allow Jamaica to exit the Federation after a national referendum voted against it. After that, Manley worked closely with the British in negotiating the terms of Jamaica’s independence. He served the rest of his political career as the leader of the People’s National Party, which was now the minority party in Parliament.

Primary sources

Representation of the People Act, 1944

With the Representation of the People Act, Britain granted Jamaica its first main measure of decolonization. This act was seen as a victory by those seeking a Jamaica less influenced by the British. However, full independence would not come for almost another twenty years.

Moyne Report, 1945

The Report of the West India Royal Commission (commonly known as the Moyne Report) detailed the results of a commission by the British government to catalog economic conditions in the colonies. The report found that economic conditions were far from ideal in the colonies from years of economic depression, and it was likely that the British were at least partially responsible. Following the report, the British government allocated funds for the colonies and granted colonies like Jamaica more autonomy over their economic affairs.

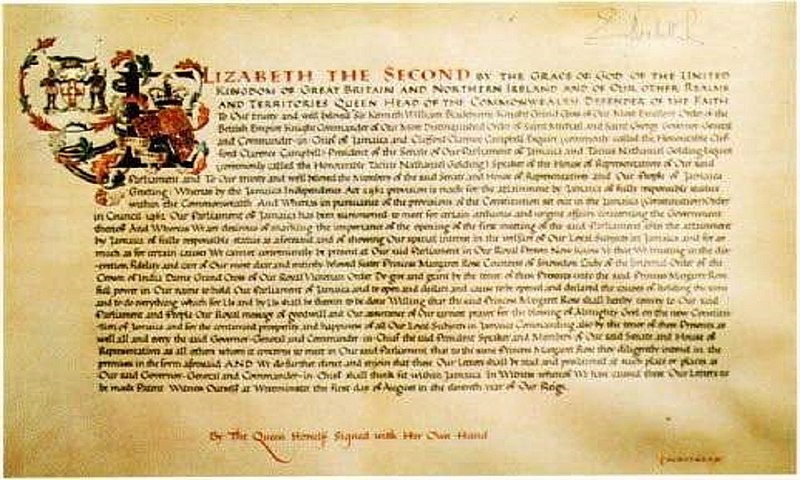

Jamaican Independence Act, 1962

With the Jamaican Independence Act, the British government finally granted Jamaica full independence and added it to the Commonwealth of Nations — a group of former British colonies turned independent nations. One revealing aspect of this act is its length: at only ten pages long, it is clear that most of the legislation providing for the autonomy of Jamaica had already been passed. By the end of Jamaica's time as a colony, the only laws which still had to be approved by the British were those relating to defense. Therefore, this act provided for little more than the formalities of Britain discharging responsibility for the new nation.

Legacy of decolonization in Jamaica

Notes on the lasting effects of decolonization

The gradual decolonization of Jamaica carried with it many consequences.

- Jamaica has dealt with decades of mismanagement and economic instability after becoming independent from the British.

- Economic stagnation in relation to neighboring countries has plagued Jamaica in the years since 1962, along with widespread unemployment, poverty, and crime

- A 2011 poll revealed that 60% of Jamaican citizens believed that that nation would be better off if it was still under British rule.

- The importance of being considered an independent nation has declined substantially among Jamaicans since the 1960’s, with nationalist fever no longer prevalent.

- Concerns about basic necessities such as food and safety have taken precedence over the desire for an independent state that was so strong decades earlier.

- Part of this instability is directly linked to the actions of the British taken during the period in which Jamaica became independent.

- Jamaican scholar Horace Campbell believes that Jamaica’s extended transition period between being a colony and an independent nation allowed the British to “reassess the local arrangements for supervising the colonial economy,” thus leaving Jamaica economically dependent on the British and unable to prosper independently.

- Jamaica became an independent nation with the responsibility of providing a strong economy for its citizens, but without the means to do this as the British manipulated Jamaica’s economic position during the transition period.

- For example, the United Kingdom entered the European Common Market (EEC) during the transition period, eliminating Jamaica’s preferential treatment in trade agreements, and beginning the process of acquiring resources such as sugar and bananas elsewhere.

- Furthermore, the Jamaican economy was highly reliant on inflows of foreign capital and imports, leaving them vulnerable to instability once ties from the British were severed.

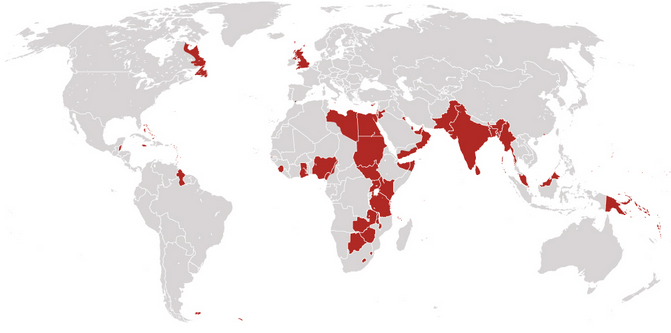

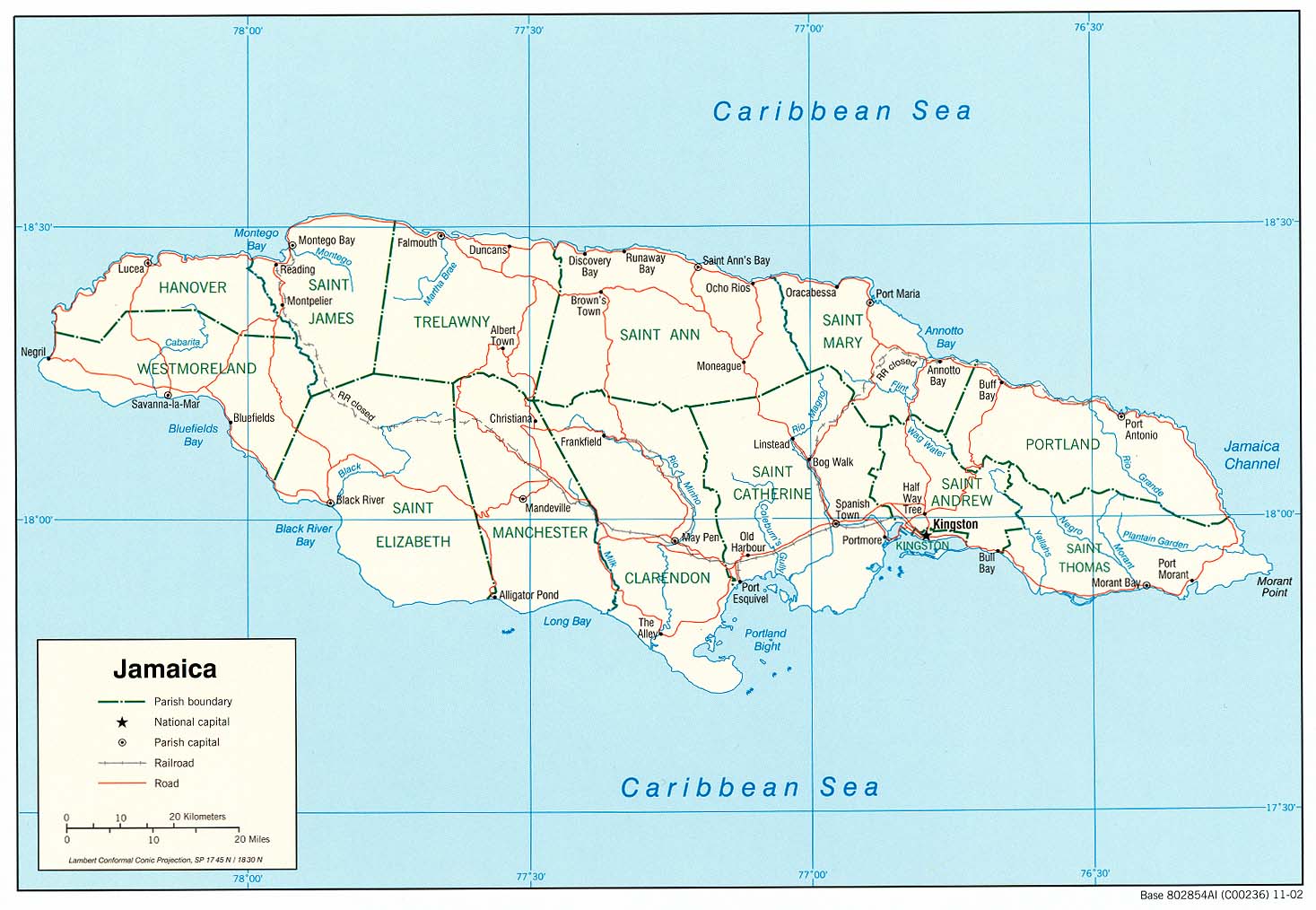

Maps pre- and post-decolonization

Conclusions

As Britain discharged responsibility for Jamaica over the course of decades, we believe the slow pace of change meant that Jamaicans never fully detached from the cultural identity of their British colonizers. Since decolonization, having an independent nation has become less important to Jamaicans than immediate needs such as food and safety; these needs have become more prevalent since independence in part due to the fact that the governmental structure of Jamaica was set up in such a way to maintain dependence on the British for support.

Bibliography

Ferguson, James A., Patrick Bryan, David J. Buisseret, Clinton V. Black, and The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Self-government of Jamaica.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Last modified September 10, 2020. Accessed March 16, 2021. https://www.britannica.com/place/Jamaica/Self-government.

The Laws of Jamaica Passed in the Year 1944. Kingston, Jamaica: Published by Authority, 1945. Accessed March 17, 2021. https://ecollections.law.fiu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1100&=&context=jamaica.

Mcnish, Vilma. “Jamaica: Forty Years of Independence.” Revista Mexicana del Caribe VII, no. 13 (2002): 181-210. Accessed March 16, 2021. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/128/12801307.pdf.

“Norman Washington Manley.” Jamaica Information Service. Accessed March 16, 2021. https://jis.gov.jm/information/heroes/norman-washington-manley/.

“Sir Alexander Bustamante.” Jamaica Information Service. Accessed March 16, 2021. https://jis.gov.jm/information/heroes/sir-alexander-bustamante-2/.

“Sir Alexander Bustamante.” Jamaica Labour Party. Accessed March 16, 2021. https://www.jamaicalabourparty.com/content/sir-alexander-bustamante.

Wallace, Kenyon. “Most Residents Think Jamaica ‘Better off as a British Colony,’ Poll Suggests.” Toronto Star, June 29, 2011. Accessed March 16, 2021. https://www.thestar.com/news/world/2011/06/29/most_residents_think_jamaica_better_off_as_a_british_colony_poll_suggests.html.

West India Royal Commission. Report of the West India Royal Commission (the Moyne Report). Photographs. British Library. 1945. Accessed March 17, 2021. https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/the-moyne-report.